On Easter weekend of 2018, I set out on a weekend backpacking trip on the Pine Mountain State Scenic Trail on the Kentucky/ Virginia border. This, despite the fact that a few days prior, I was packing for the trip while looking out my window at 9 inches of snow on the ground. This, despite the fact that the great world wide web was eerily silent on the report of people who actually had done this trip.

The Pine Mountain Trail of Kentucky (not to be confused with the one in Georgia) boasts a website extolling its virtues, as well as maps, phone numbers of shuttle drivers, and a “Join Our Efforts” page—last updated in 2016. http://www.pinemountaintrail.com/ . Once completed, The Pine Mountain Trail will be part of the planned Great Eastern Trail, which one day will parallel the Appalachian Trail to the West, offering an alternate long-distance route through the Appalachians. The Great Eastern Trail is a work in progress, as is the Pine Mountain Trail, so I chose a section, the Highland Section, that was reputed to actually exist. Random scatter shot across the web that briefly mentioned this trail mainly come from at least three or more years ago, with phrases like “not ready for prime time,” and “no shelter actually built yet.” One tourism article did urge readers to go out and hike the trail, but it didn’t seem like the writer had actually done so; another article proclaiming positive fact about the Pine Mountain Trail also claimed that the Appalachian Trail went through Ohio. I was naturally wary, yet a road trip this summer through Kentucky with my family had led to a brief venture on another section of the PMT, and I had been curious to find out more. Three votes and a handful of photos on hiking project, plus a you tube video, tipped the scales in the PMT’s favor. https://www.hikingproject.com/trail/7020932/pine-mountain-trail-highland-section

I did this trip as an Out-and-Back from the trailhead at US 23 to Flamingo Shelter (just shy of US 119). The trail does in fact exist and I completed my planned trip successfully.

As far as I can tell, the best maps available of the PMT are the ones provided for free by the Pine Mountain Trail Conference. Print these out before you leave home and add my notes to it before you go (read below). Also download maps and directions on google maps on your smartphone or GPS before you go so that you can get to and from the trailhead (I didn’t have cell service for part of my trip). PMTC’s maps tell you to “Continue on US-23 until you reach the Kentucky/Virginia state line.” Well, yes, but here’s a little more information:

The trailhead on US-23 is by the Marathon Gas Station on the same side of the road. (There is also a Valero station on the other side of the road. Don’t park there.) The address for the Marathon station is: Black Diamond Market #69/ Marathon Gas, 12643 Orby Cantrell Hwy. The gas station is open 24 hours and is a popular stop for trucks. When you park, be sure to park way in the back, on the gravel/mud. The lined spots on the pavement are for customers, and there are signs warning that you will get towed if you keep your vehicle in one of these spots for more than an hour. Across an ugly, barren expanse of mud (or dirt, I suppose) you will see a large sign, which is the very obvious trailhead for the PMT.

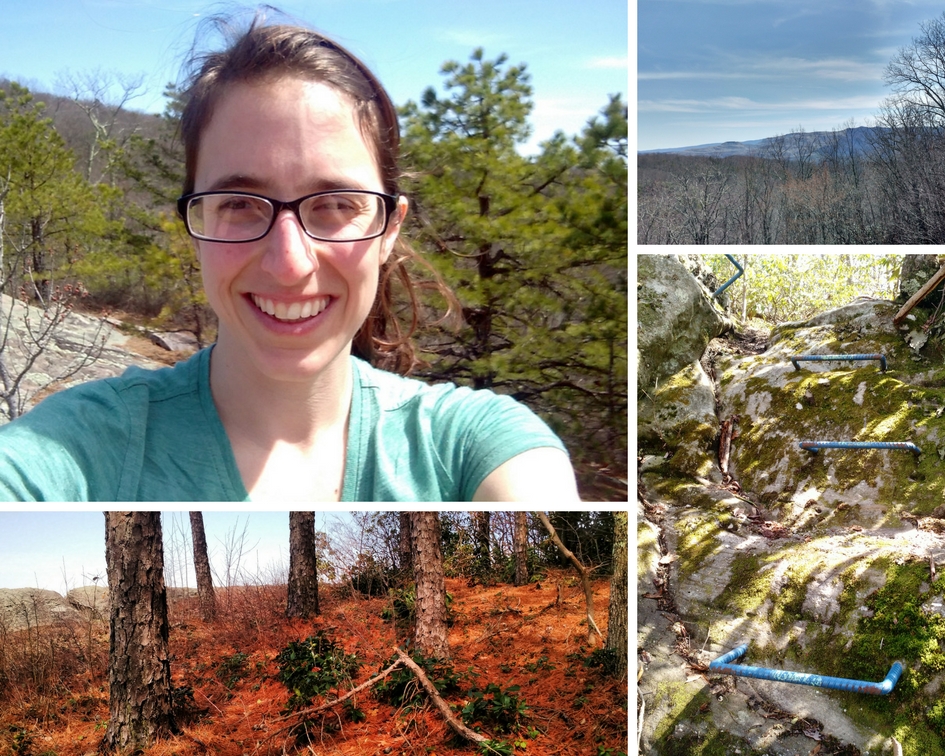

Clockwise from top left: me at the trailhead; the first steps of the trail; the moss-covered trail; evening on the trail near US 119

As this section begins, the Pine Mountain Trail literally glows- with a green moss the grows on and next to the trail, highlighting the trail ahead and behind you as you walk. Look carefully, and you might also spot some tiny and beautiful light pink or white flowers. On Friday evening, I traversed the 1.3 miles from the trailhead to the first allowed camping spot, Jack Sautter Campsite. Because the gas station is at such a high point, the walk was an easy one. A few streamlets run across the trail between the Trailhead and Jack Sautter Campsite, but all are dry crossings. The campsite is in a gap, which is not ideal on cold nights. When night falls, the warmer air above the gap cools, rushing down to the gap, where it pools, creating a nice little refrigerated microclimate. The wind, meanwhile, finds a break in the mountain, rushing in to create a small wind tunnel. I spent a very cold night in the gap and when I awoke in the morning, the ground was covered in frost. The campsite is signed, has a central meeting area with a bear pole and a campfire circle, four tent pads that are also signed (continue walking along the PMT less than a minute to find #3 and #4), plus other flat areas behind the campfire circle that could potentially be used in the future. With bare trees, a few lights and a little road noise can be seen and heard from the campsite, but it is not distracting. A rutted .2 mile road promises to lead down to water at the Old Meade Homeplace, which in fact it does (perhaps slightly longer than .2) A charming meadow next to a small stream is more attractive than the campsite itself.

In the morning, I packed up and hiked the 0.9 miles to the first overlook, Twin Cliffs, which is a short trip (perhaps .05) off the PMT, where I made breakfast. If you are in need of water, right before twin cliffs a small spring-fed stream is your last chance to get water until Indian Grave (at least). Twin Cliffs offers two views. The first cliff offers a view into Virginia; follow the blue blazes to the second cliff for a look into Kentucky. I was all alone up here, and it was beautiful. Back on the PMT, below Twin Cliffs is Fortress Rock. One of the things I love about Kentucky and Western Virginia is all of the unique geological formations that you simply don’t see to this extent further east.

Clockwise from top left: view from first cliff at Twin Cliffs; cairn on Pine Mountain Trail between Jack Sautter Campsite and Twin Cliffs; view from second cliff at Twin cliffs; blue blazed trail leading up to Twin Cliffs

Pink flowers, cool moss-covered trail, awesome little meadow, Twin Cliffs, Fortress Rock—all in a little over two miles. But –BAM!—just when you’re thinking maybe this is going to get really good, it stops. The next two and a half miles to Indian Grave Campsite are uninspiring. Shall I say monotonous. Yes, boring. Dull. Call it what you will. Put some miles under your feet ‘cause there’s no reason to dilly dally. Actually, the going doesn’t start to get really interesting again until right before Adena Spring Shelter. You’ve got about four and a half miles to go through plain hardwood forest with little undergrowth, which looks and feels a little creepy. Some of the time you’re following a ridgeline—in the summer I can imagine this is murderously hot and doubly frustrating knowing the trees are blocking all of your views. Much of the trail is on rutted old road beds. The only saving grace of this section is that without undergrowth, it’s easy to spot wildlife. In this area (either out or back), I saw four white tailed deer, two wild turkeys, two chipmunks, five squirrels, four hawks, and two ground hens. This trail also borders some private land, so you’ll also see hunting stands—one of which had the most precarious ladder I have ever seen actually intended for use. Many of the gaps are signed in this area, though they are not necessarily named on the map, so you’ll have to do a lot of cross referencing with the elevation profile and map to figure out where you are. My advice is: don’t bother. Just keep walking.

Clockwise from top left: sign for Poplar Holler; sign for Bob Simmons’ Cave; ho-hum stretch of trail; the pipeline

It is important to note, however, that Indian Grave Gap and Indian Grave Campsite are two different places. Both are signed, but the sign for the campsite had fallen off the post and was laying on the ground when I got there. The campsite surprised me in other ways, too. Although there was a sign for water, I didn’t see any obvious signed or unsigned path there (or water). I didn’t need water, so I chose not to explore. I don’t know if there is really water down the valley, or how far it is if it is there; however, at no other point in this hike did I come upon a situation where water was promised idly. I think there is probably water. There’s also probably some flat spots if you really look around, maybe more promising if you walk a minute or two up the trail from the sign. While I wouldn’t go so far as to say you shouldn’t camp here, don’t expect the bear pole and tent pads of Jack Sautter, and be sure you have a little extra time for exploring.

After Indian Grave Campsite and a gap named “Poplar Holler” you will soon reach another big rock, also with signpost. Look around for “Bob Simmon’s Cave.” If you’re small and not afraid of getting a little wet, you can scrunch around to the back of the cave, which is still in the process of forming as water drips onto the sandy floor of the cave. I loved to see all of the holes that erosion has worn away inside the cave.

Before Adena Spring Shelter, you will also start to see signs saying “CAUTION: Pipeline Gas.” The trail follows a pipeline access road for a little way, and you will be walking next to it. About twelve inches in diameter, it rests innocently on the ground, at times half buried in the leaves. The weekend before this trip the area had a heavy snow storm; followed by wind, trees and branches fell to the ground. Only a small pine tree leaned over the pipeline, but I don’t like to think about the effect of a larger tree. This pipeline is only one of the reasons why camping is allowed only at designated sites on this section of the Pine Mountain Trail.

The climb going up before Adena Spring Shelter wouldn’t be too rough except that here the pipeline road turns to rock surface coated in water, which can be very slippery. At the top I found a large puddle with more frog eggs than I have ever seen in one place, as well as a few very small tadpoles wiggling around. I wonder if they were from a hatch that somehow survived the snow(!?)

Adena Spring Shelter is solidly built, surrounded by rhododendrons with a sheltered feel. There is a campfire circle, covered picnic table, and bear pole, as well as a moldering privy with a dutch door and a view to look out on. There are no flat spots available for tent camping at this shelter. I was surprised to see how much stuff was left in this shelter: a handful of sleeping pads (one must have been from a couch or something, it was six inches thick), a bivy, two metal grills and a cast iron skillet, a pillow that had become a mouse toilet/home, a broken headlamp, etc, etc. The tag on the couch cushion/sleeping pad identified it as a trail maintainer’s with PMTC. I was surprised about this because most trail maintenance groups take more of a “leave no trace” policy. Leaving items in the shelters encourages others to do the same and can lead to a very “junky” shelter in no time. That being said, are you going to begrudge a tireless volunteer their couch cushion, not if its absence would be the only thing between them and several hundred more trail maintenance hours? Didn’t think so. However, that is not an invitation for you, the trail user, to start using the shelter as your private clubhouse. You leave something, someone else leaves something, and the next thing you know the mice think everything is theirs. Which it will be.

Clockwise from left: the well-signed Pine Mountain Trail; frog eggs galore!; precarious tree stand; Adena Springs Shelter and bear pole

Both springs below Adena Spring Shelter are beautiful piped sources. The second is a very short walk off the trail while the first is right on the trail and convenient to the shelter. Now, if you look at the map, you will note that there are NO water sources marked after the two near Adena Spring Shelter. If you’re doing an Out-and-Back with an overnight at Flamingo, this might cause you to think that you need to bring enough water with you for not only the rest of the day, but that night AND the next morning until you get back to the springs near Adena. You might do something crazy, like load up with six or more liters of water. DON’T DO IT! There is actually a lot of water between Adena and Flamingo, even if it isn’t marked on the map, with some right near your overnight stop at Flamingo. You do need some water to get you through the next four plus miles, which are dry and offer lots of opportunities for whiling away the day, but this is not the Pacific Crest Trail here.

If on the climb up to Adena you started getting an inkling that things were about to get good again, what with all the rhododendron around, you were right. Prepare yourself for endless, gorgeous views, unique and beautiful plant life, and even some more interesting rock formations. All this, and there are NO extended climbs to suffer through. You just walked right into hiker paradise, my friend.

First up is Stateline Knob—even though a viewpoint icon is on the map, you won’t get much of one that isn’t covered in trees. Just 0.1 away, however, is Wildcat Rock, which will offer the real deal, even in the summer when the trees are no longer bare. I stopped here to have lunch and didn’t regret it. There are a few more minor views along the trail, some of which are listed on the map, and some which aren’t. Mayking Knob, though, isn’t worth a stop, as its main feature is another treed-in view and a lot of high frequency radio equipment. But Slip & Slide Rock, Swindall Campsite, and Box Rock are all worth a stop. It starts to feel a bit indulgent, I know. But it’s why you’re out here, right? Are you going to enjoy it or just breeze on by? Swindall Campsite is definitely the most scenic campsite on this trip, and I would be tempted to stop here, even though the site is a bit sloped. Because it’s a dry site, it’s not a safe place for a campfire, so you shouldn’t have one. However, with those views, who needs one? The moon was bright on my trip, and I would have loved to see it from Swindall! Hammock hanging is also an option. Perhaps Mar’s Rock, with its red, pitted, other-worldly surface and expansive views looking into Kentucky is the most memorable of the trip, though truthfully it is hard to pick a favorite. High Rock is also stunning. When you’ve had enough (can there ever be enough?), you can head on to appreciate some rock formations.

Clockwise from top left: Enjoying the view near Box Rock; the view from Slip & Slide; iron bars on the trail; hammock hanging opportunities at Swindall Campsite

Enjoy the cool descent down to one of these formations, the “Lemon Squeezer,” where the trail slips between two boulders. It’s just large enough for a person to fit through, though I did have to take my pack off and carry it above my head. You can also fill up on water not far from the Lemon Squeezer. Between the Lemon Squeezer and Eagle Rock is a small knob, Blueberry Cliff (unmarked on the map) which boasts yet more views. Eagle Rock is another example of the unique Vertucky rock formations. A rather flat arch that spans the gap between two hillsides, it’s triangular top is not quite like anything I’ve seen before.

Clockwise from top left: view from Blueberry Cliff; the sign pointing the way to High Rock; the Lemon Squeezer; Eagle Rock

Before you get to Flamingo Shelter, you’ll pass yet more water. The last source is about .2 below the shelter, so it’s worth filling up and then continuing your climb instead of making a second trip. Although Flamingo Shelter is relatively close to a road, it didn’t feel like it, and was actually less junky than Adena Shelter. A tin flamingo, painted pink, adds a bit of flair. The shelter is a copy of the one at Adena, and so is the privy (though without the view). There is a campfire circle and bear pole as well. The location of this shelter is ideal. It is open enough to feel welcoming, yet sheltered from the winds. In the night, I woke up once to hear wind roaring around me, but did not feel any where I had set up my tent. I was able to have a much warmer night than the one previous, and I was grateful for it! Yes, there is room for a few tents near the campfire area, with spots that are fairly flat and still not too hard and packed down.

Clockwise from left: approaching Flamingo Shelter; the privy; paint and reflector blazes on the trail; tent camping at Flamingo Shelter

The next morning I woke up and did the whole thing again, but in reverse! I never walked the .4 miles from Flamingo Shelter down to US 119, so I do not know what that trailhead looks like or what that short section of trail offers. Which direction did I like best? I think I liked going from US119 to Flamingo best, as I did on the first day. Although I made better time on the way back (Likely due to the fact that I wasn’t carrying excessive amounts of water), it is the latter part of the trail that is more interesting. Getting the ho-hum stuff out of the way in the morning, when I felt fresh enough to speed on by, and having a lot of good excuses to dilly-dally along the way in the afternoon, when I am more tired, felt like a good fit for me.

The Highland Section of The Pine Mountain Trail is extremely well-marked. The trail used to be blazed using yellow and/or green paint blazes, which have been replaced with neon reflector blazes, such as you would see on driveways along busy roads. Blazes are frequent, and signage exists anywhere there could possibly be confusion. Along the way, you may also see red blazes (where the PMT and another trail coincide, or other color markings on trees (i.e. red stripes) that denote boundary lines. I actually don’t think I’ve ever been on a trail this heavily marked before, and if you get lost I will be very, very surprised.

The trail was beautifully moody the second day. On the left is the approach up to Mars Rock; on the right, one of the pine trees that gives the trail its name.

So would I recommend this hike? Absolutely! (Though I can imagine it would be hot and muggy in the summer, and I am glad I hiked it in the spring; fall also has potential.) On the second day, as I surveyed the land from the immense expanse that is Mar’s Rock, with its unhindered view, I was suddenly struck not only with the beauty of the trail but with the ridiculousness of what I was experiencing. Here we have cliff after cliff after cliff offering expansive views, a well-marked trail, and even a loop option for day hikers (visiting only a couple of the views) and shelters for backpackers. On this entire trip, I saw three people. Closer to where I live, there are some highlights of the Appalachian Trail: McAfee’s Knob and Tinker Cliffs. Literally hundreds of people will hike these sections each weekend. On the Pine Mountain Trail, I felt like I had entered some alternate, people-less universe. Of course, the Pine Mountain Trail is not a part of the Appalachian Trail; the Great Eastern Trail will perhaps one day, when complete, raise this section’s profile, but for now you should take advantage of this secret gem that’s just a bit further from the East Coast’s major metropolitan areas.

Wintergreen berries, ferns, and moss along the trail; pine trees with a view; Nature Conservancy signs reveal yet another reason for camping in designated spots only!

Trail miles: Day One: 1.3

Day Two: 13.0

Day Three: 14.7 (includes side trip down to Old Meade Homestead)

Snack o’ the trail: Dill Pickle Chips (Who ever heard of a trip to Vertucky without some dilly beans? Sadly, they’re not really packable, so this was my backpacking version)

Solitude: High

Ease of Navigation: Easy

Beauty: Mostly high with some low spots

Difficulty: Medium